Loading content gate...

This essay is the second in a two-part series examining Umurangi Generation and it’s relationship to trauma and memory. Read the first part here.

It’s 2020. The police give us 10 minutes to disperse. Turning to my friend, we begin to talk through our plan to leave. 3 minutes pass, and he gets shot in the chest with a tear gas canister. The next day, the news shows the chaos and destruction of angry protesters. My friend’s massive purple bruise and broken ribs won’t be reported on.

It’s 2024. Protesters stand outside a meeting of powerful assholes chanting angrily, but remain on their side of the barricades. The people we came to yell at leave safely. No dispersal warning is given. The police begin swinging bikes at protesters to clear us out. When that doesn’t work, they turn to pepper spray. They claim we deserve this due to our “violent” response of losing our balance falling on them. Nevermind the bikes which knocked us over in the first place. The next day, the news reports on the ways protesters “assaulted police officers,” leaving out the broken fingers and burnt eyes of my friends.

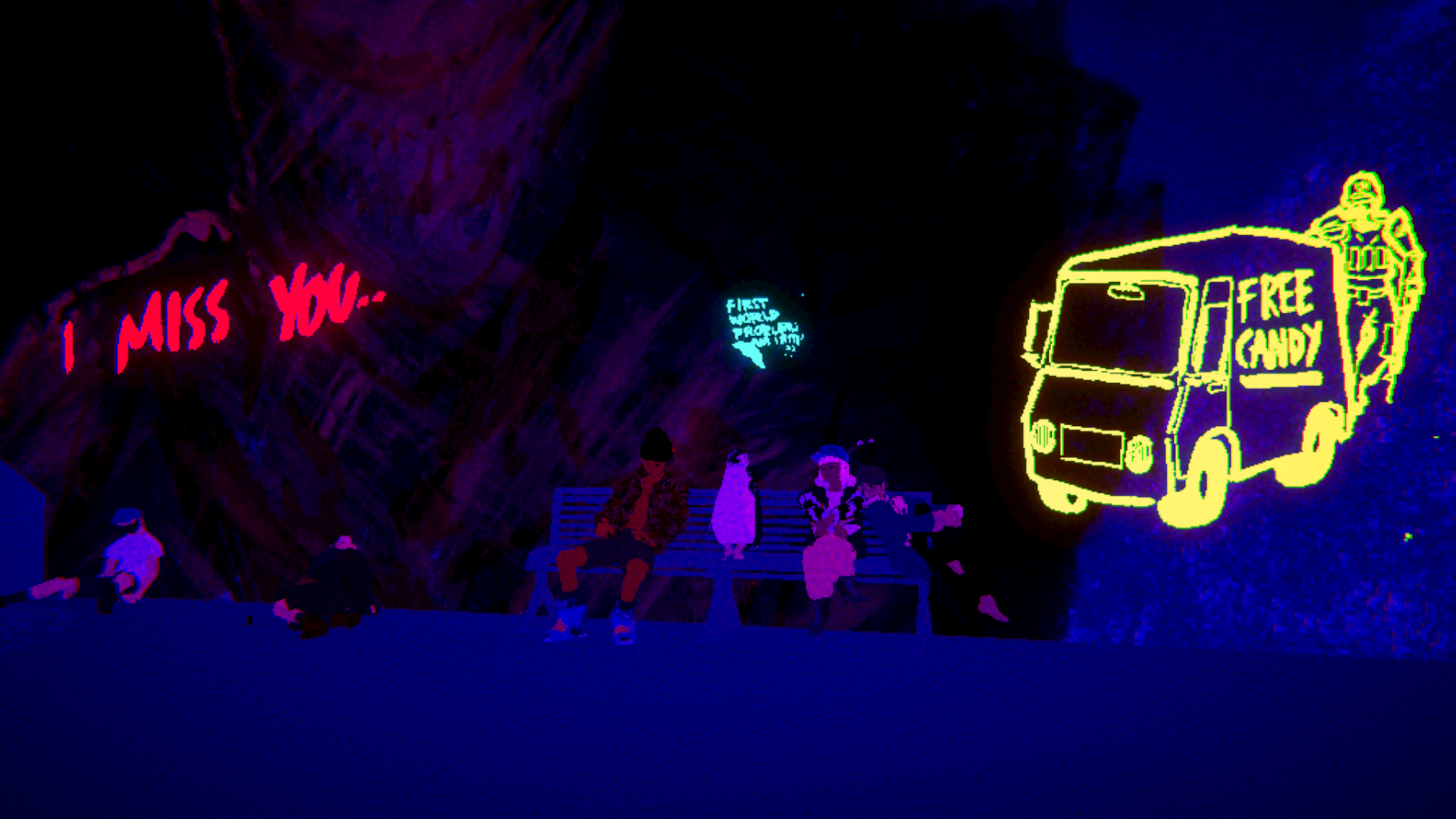

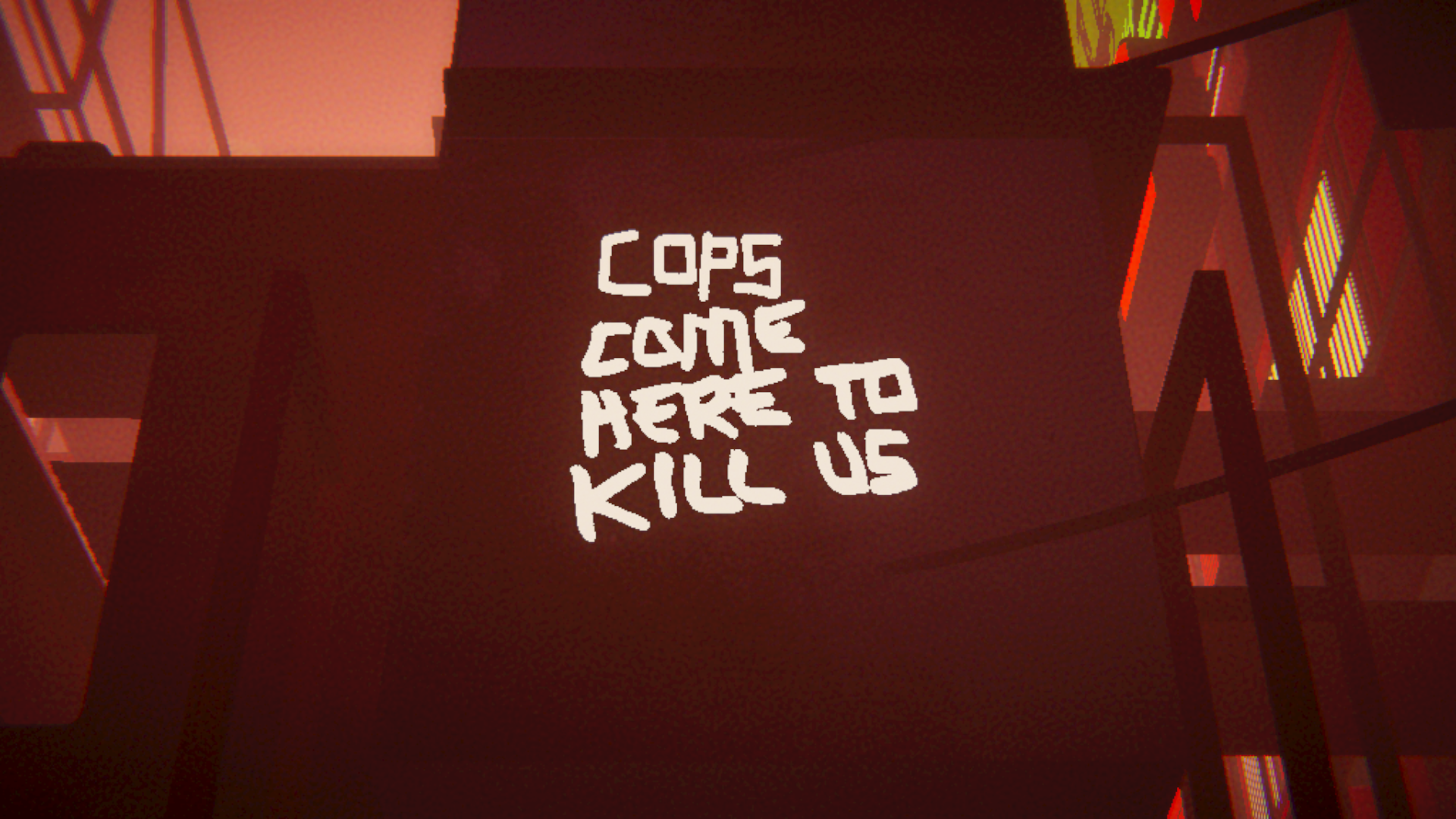

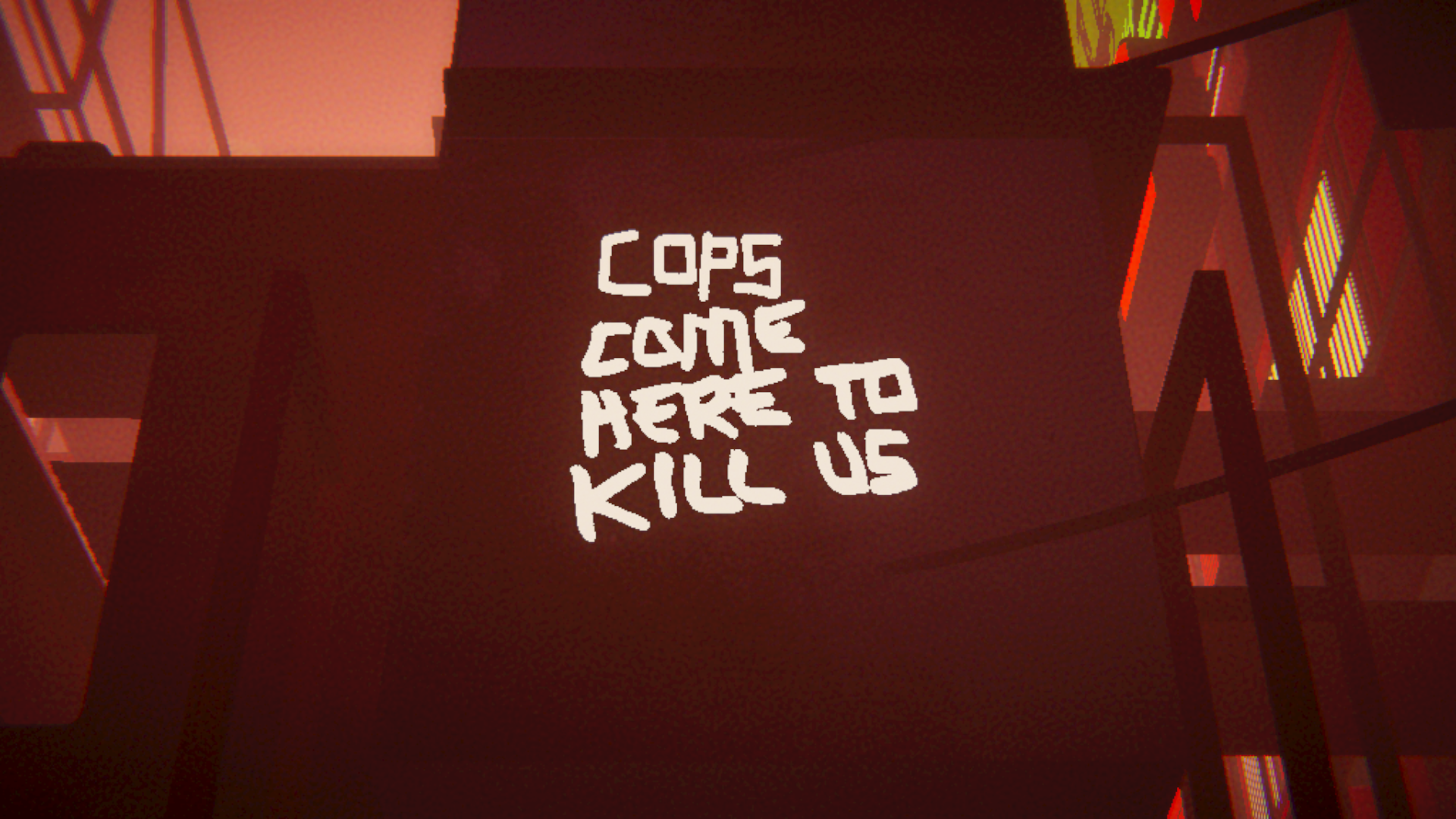

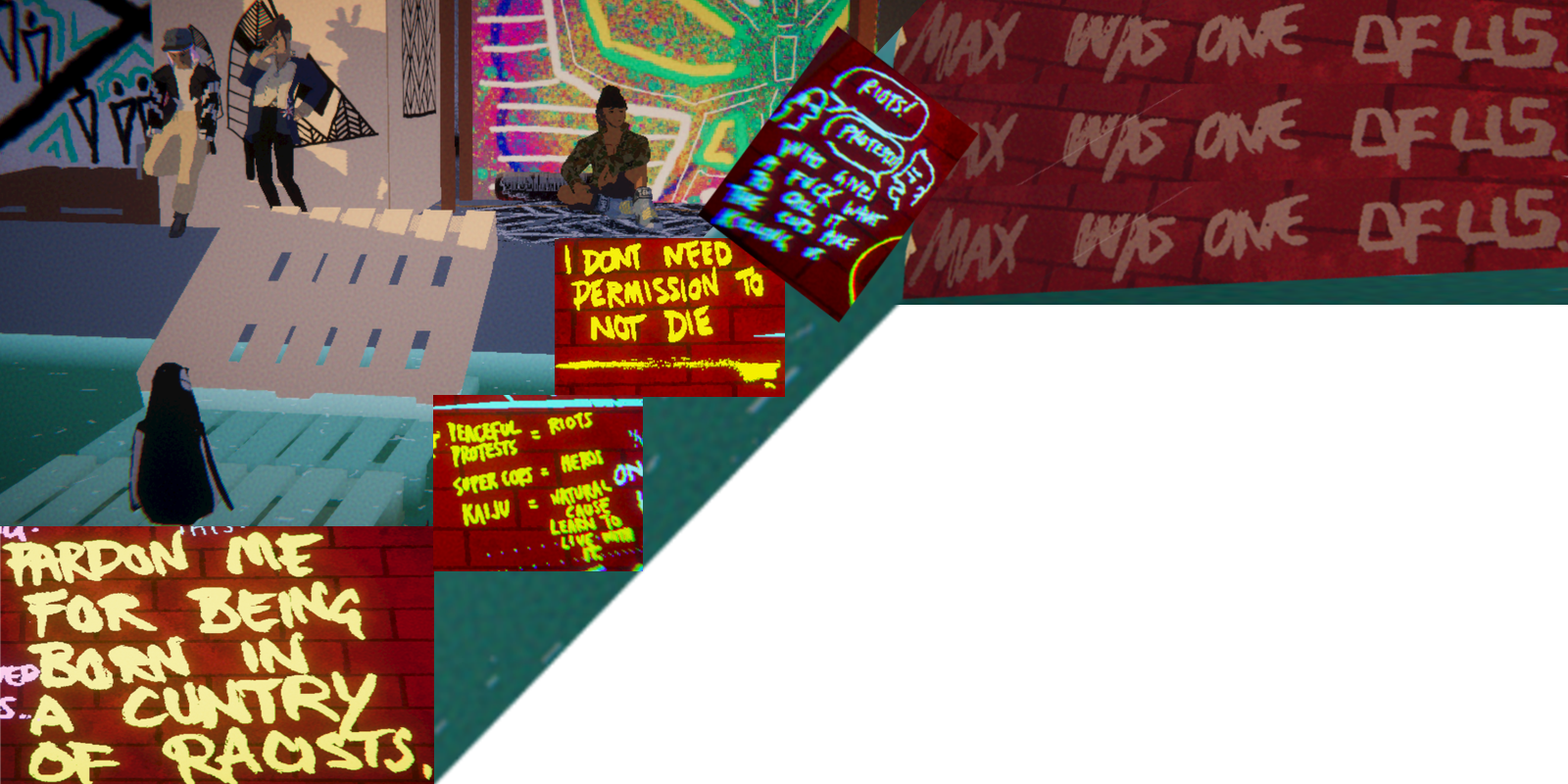

It’s 2021, and Umurangi Generation asks me to take a picture of the word “cops.” Searching around, I find some graffiti that says, “cops come here to kill us.” I take a photo from afar, but the game doesn’t register it as completing the task. It wants a close-up. I move closer so that only the phrase is in frame. Nothing. I keep taking pictures, inching further and further in until I get so close that the only graffiti left in the picture is the word “cops.” Finally, the game tells me I’ve done it.

The photo remembers the cops were here.

The photo has forgotten what they did.

I stare at the photo and Caruth’s words rattle through my head, telling me that forgetting is inseparable from remembering. It is a necessary part of understanding, and “a freedom that is fundamentally a betrayal of the past.”i Photos always forget. They always cut something out of the frame, and that edit almost always serves the state, settler, and white cishet supremacy. Everyone remembers the famous book burning photo of the Nazi’s, few remember that the books were from Magnus Hirschfeld’s queer haven The Institute of Sexology.ii Everyone remembers that Martin Luther King Jr. fought racist injustice, few remember that he did so by advocating for socialism.iii Everyone remembers the pictures of October 7th, 2023 in Palestine, and if modern popular media has its way, few will remember the decades of Palestinian oppression that preceded it,iv or the genocide that came after.v

As I try to remember what actually happened in Umurangi Generation, I find myself missing pieces.

The United Nations are heroes!

We are winning the kaiju war!

No one knows where the kaiju come from!

As I try to remember why I actually decided to show up at this protest, I find myself missing pieces.

The police are our heroes!

America is an exceptional country!

No one knows why we're running out of water!

Sontag knows the treachery of images well. She tells me “there is no war without photography… ‘shooting’ a subject and shooting a human being. War-making and picture-taking are congruent activities.”vi She notes the ways a mix of ‘good taste’ and state censorship act as a selective forgetting in favor of wartime efforts. I start to roll my eyes at how on the nose she’s being, before remembering that the first rapid-shot camera was a gun.vii

I sit in front of my computer at who knows what time. I’m tired, and some politician, or billionaire, or facist has committed some xenophobic, or transphobic, or racist atrocity. Maybe all of the above and more. I forget the exact event, but viscerally remember the feeling.

The specifics don’t matter anyway. To pass the time and the depression, I open the folder which has all the pictures I have taken in Umurangi Generation. As I scroll through, I see all the little ways that the each level pushed me to photograph some things and to forget others. My friend’s experiences are ignored and story of the state shines through, leaving us to bear the trauma of memory.

I stare at the word “cops,” A flood of tear gas and pepper spray enveloping me.

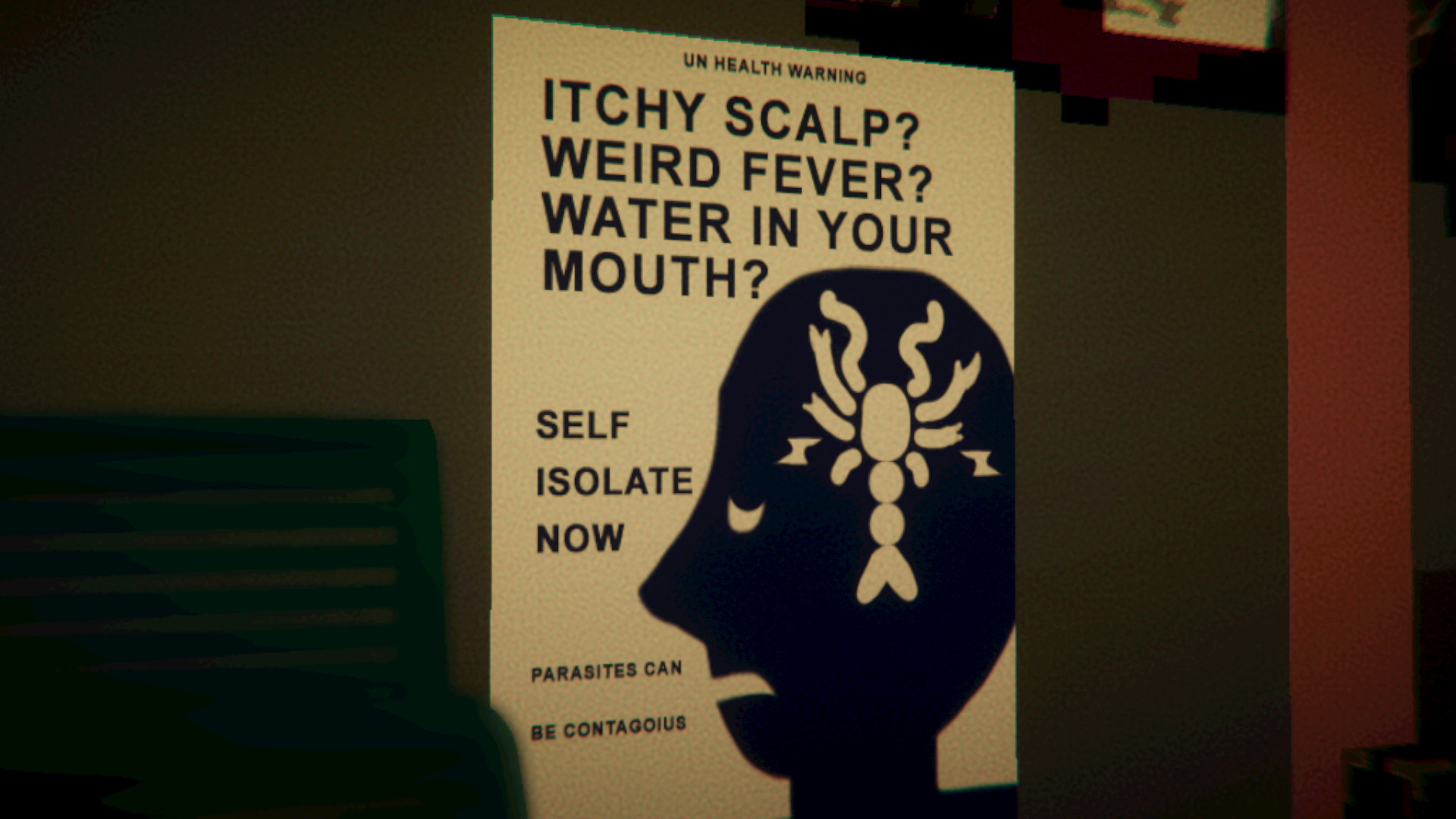

Until I close the folder and see my desktop background. It’s a picture of a poster I found in Umurangi Generation that says “Itchy scalp? Weird fever? Water in your mouth? Self isolate now: parasites can be contagious.” I did not take a picture of this poster for any in-game goal; I took the picture because it made me laugh. The U.S. was experiencing some of its highest Covid rates at the time, there was no vaccine in sight, and I was stuck alone in my apartment in a brand new city. Piles and piles of bullshit surrounded me, and yet I remember laughing so hard my neighbor knocked on their ceiling.

I start the game up again.

As I move around each level with fresh eyes, the words of Pedri-Spade appear in every shot: “they were never only the master’s tools.”viii Photographs may forget, but they are nonetheless technologies of memory which, when used with care, can “help individuals claim hidden or lost histories… springboard to new ways of how to think about and move through history… [and] serve as sites where oppressed and Indigenous peoples explore issues related to identity, self-representation, and alternative ways of being.”ix Umurangi Generation does not deny the critiques of image-memory made by Sontag or the betrayals of forgetting presented by Caruth. Instead, the game asks us to sit with those critiques and see if we can find a way through. Umurangi Generation hands me the camera, shows me the immense amount of power that comes with it, and asks how I would take the last few photos of my existence.

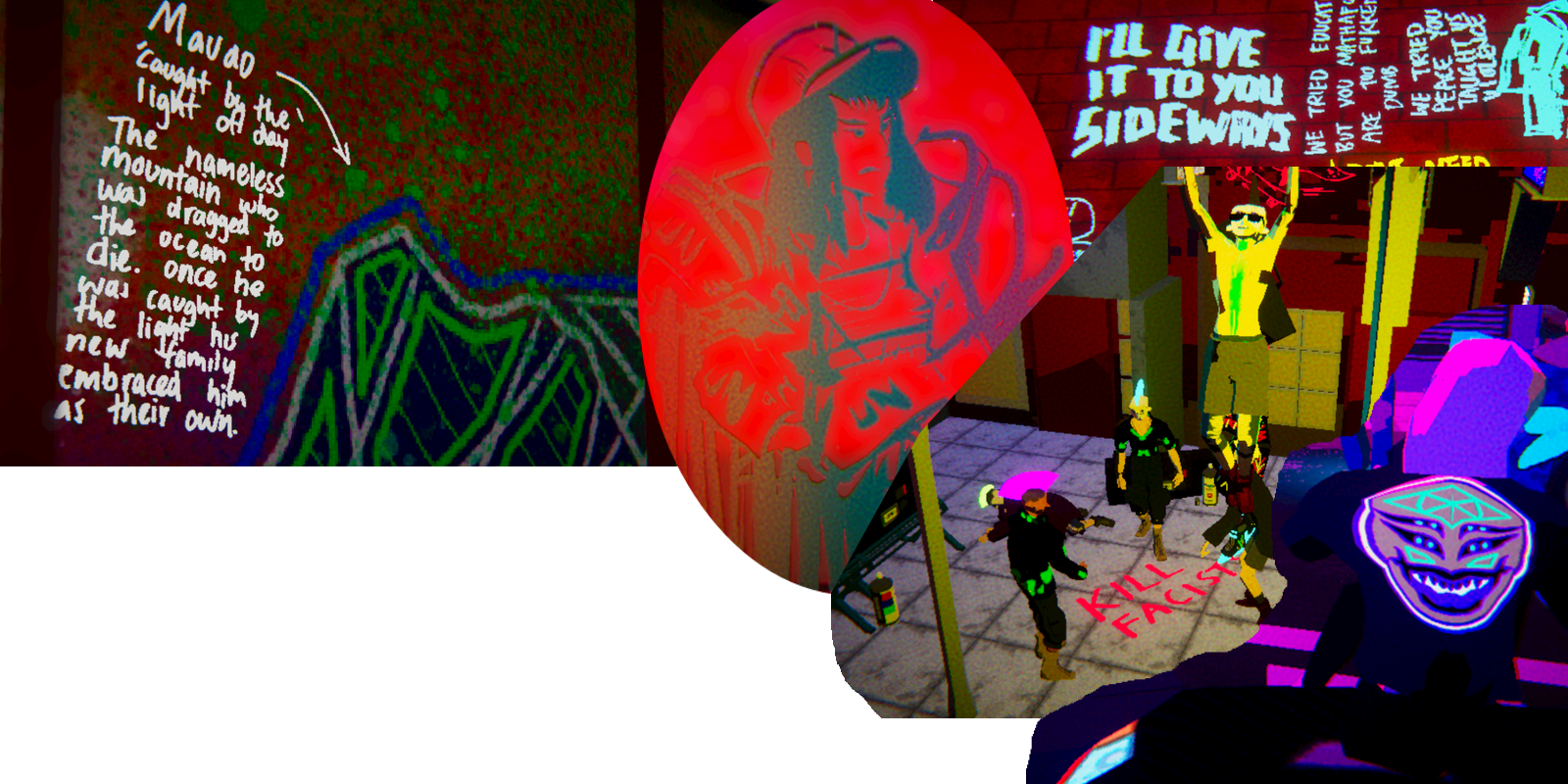

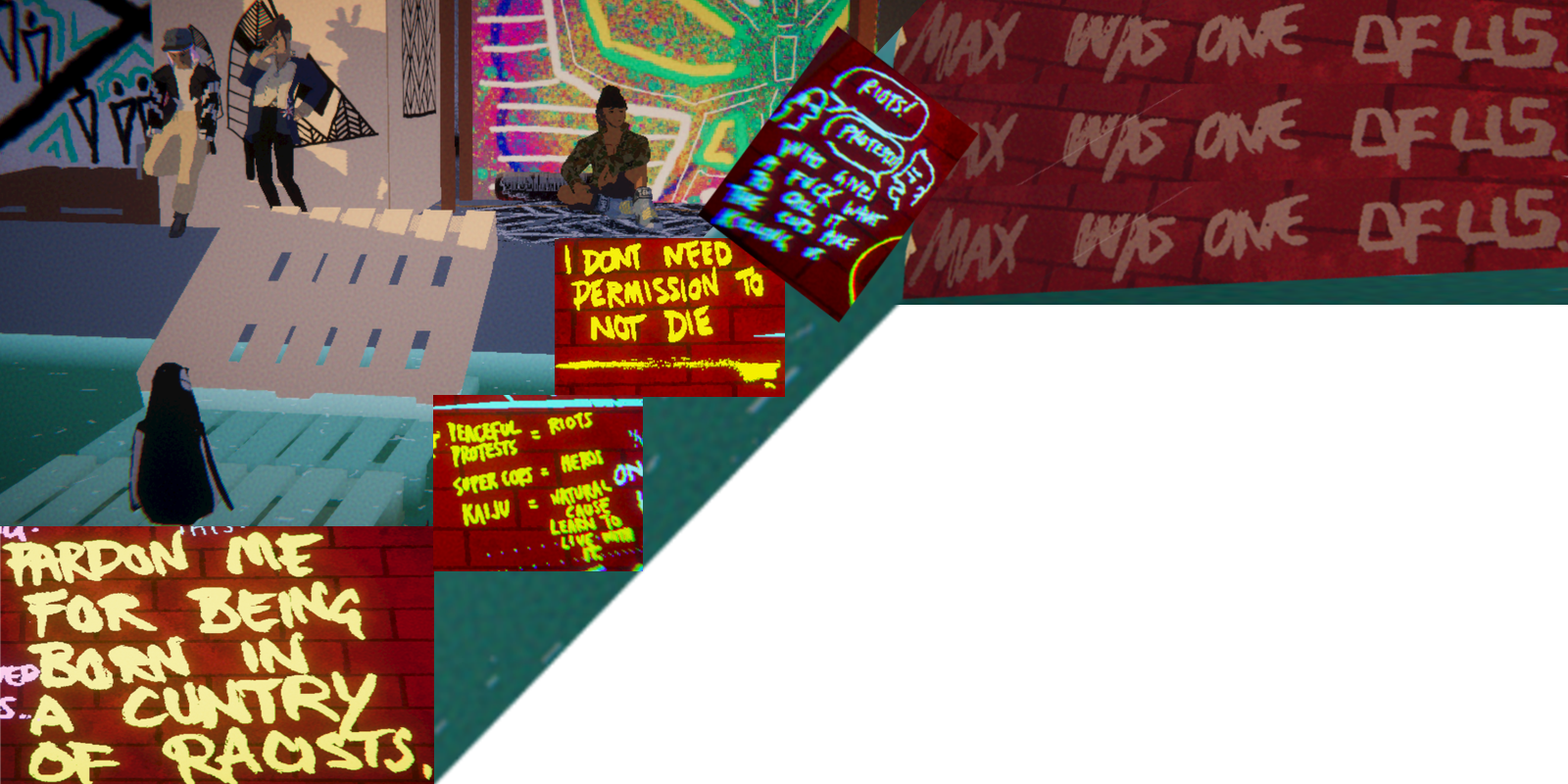

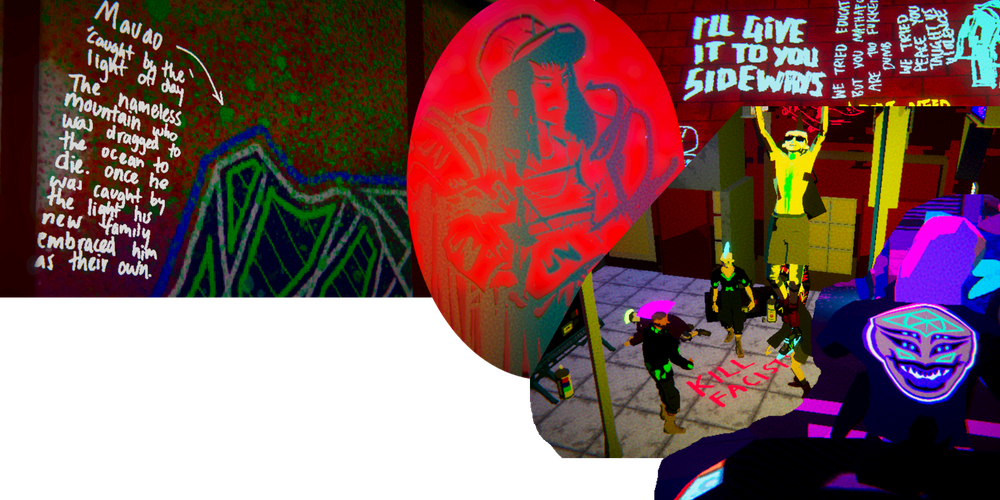

Running through Umurangi Generation again, I take pictures of people dancing in the street, of the graffiti on the walls, and of the history of Mount Mauao. My first run through of the game, I strictly followed the goals I was given and found a story of state violence and media ignorance. From it, I created a selective narrative of trauma, presenting this last generation as solely defined by damage. Tuck and Ree once warned me, “Damage narratives are the only stories that get told about me, unless I’m the one that’s telling them.”x I flattened the people of Aotearoa to one traumatic dimension, overlooking the vibrancy of a community filled with joy. A community filled with something to fight for.

In 2020, I remember making signs with friends, joking and talking about anime as we prepared to take to the street. When my friend was hit with a tear gas canister, a complete stranger helped get him out and checked his wounds. In 2024, I remember sharing meals, stories, and resources with organizers in the weeks leading up to the protest. After the pepper spray was unleashed, I began to have a panic attack. A stranger in black bloc guided me to a safe place before leaping back into danger to help others.

In the last level of Umurangi Generation, we protest U.N. occupation. We make art, we perform rituals, and we tell the U.N. all the ways they are making the problem worse. As payment, they sick their giant mech on us. One of the riot police cracks me on the head with a baton, and I pass out.

I awake on the roof, my friends having dragged me to safety. Our little protest of a few dozen people cost the U.N. millions, and our graffiti lines the walls of the now bombed out streets. I see that I can now take a selfie with my camera and, before I leave, I get one more photo with all my friends in it.

This is how they will be remembered. The Umurangi Generation will not be defined solely by their trauma. They will not be defined by the state’s narrative. They will be defined by the care, the love, and the desire they showed in the face of the end of the world.

Citations

i Cathy Caruth, “Literature and the Enactment of Memory,” in Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 33.

ii Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, https://hmd.org.uk/resource/6-may-1933-looting-of-the-institute-of-sexology/

iii Sylvie Laurent, “MLK Was an Exemplar of a Black Socialist Tradition,” Jacobin, April 4, 2023, https://jacobin.com/2023/04/martin-luther-king-jr-mlk-socialism-class-racial-justice-civil-rights-movement

iv Hagar Shezaf, “Burying the Nakba: How Israel Systematically Hides Evidence of 1948 Expulsion of Arabs,” Haaretz, July 5 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2019-07-05/ty-article-magazine/.premium/how-israel-systematically-hides-evidence-of-1948-expulsion-of-arabs/0000017f-f303-d487-abff-f3ff69de0000

v Wafaa Shurafa & Samy Magdy, “Palestinian death toll surpasses 70,000 since start of Israel-Hamas war, Gaza ministry says,” PBS News, November 29, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/palestinian-death-toll-surpasses-70000-since-start-of-israel-hamas-war-gaza-ministry-says

vi Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 1st ed (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 66.

vii Lily Alexandre, The Psychic Burden of Being Watched, Produced by Vic Mongiovi, Cinematography by Sasha Boudreau, Script editing by talah, November 23, 2025, 53:31, https://youtu.be/gStjfje6Mq4?si=mjwULbFbrRNtyZnc

viii Celeste Pedri-Spade, “‘But They Were Never Only the Master’s Tools’: The Use of Photography in De-Colonial Praxis,” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 13, no. 2 (June 2017): 106, https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180117700796.

ix Pedri-Spade, 107.

x Eve Tuck and C Ree, “A Glossary of Haunting,” in Handbook of Autoethnography, ed. Stacey Holman Jones, Tony E Adams, and Carolyn Ellis (Left Coast Press Inc., 2013), 647.