Loading content gate...

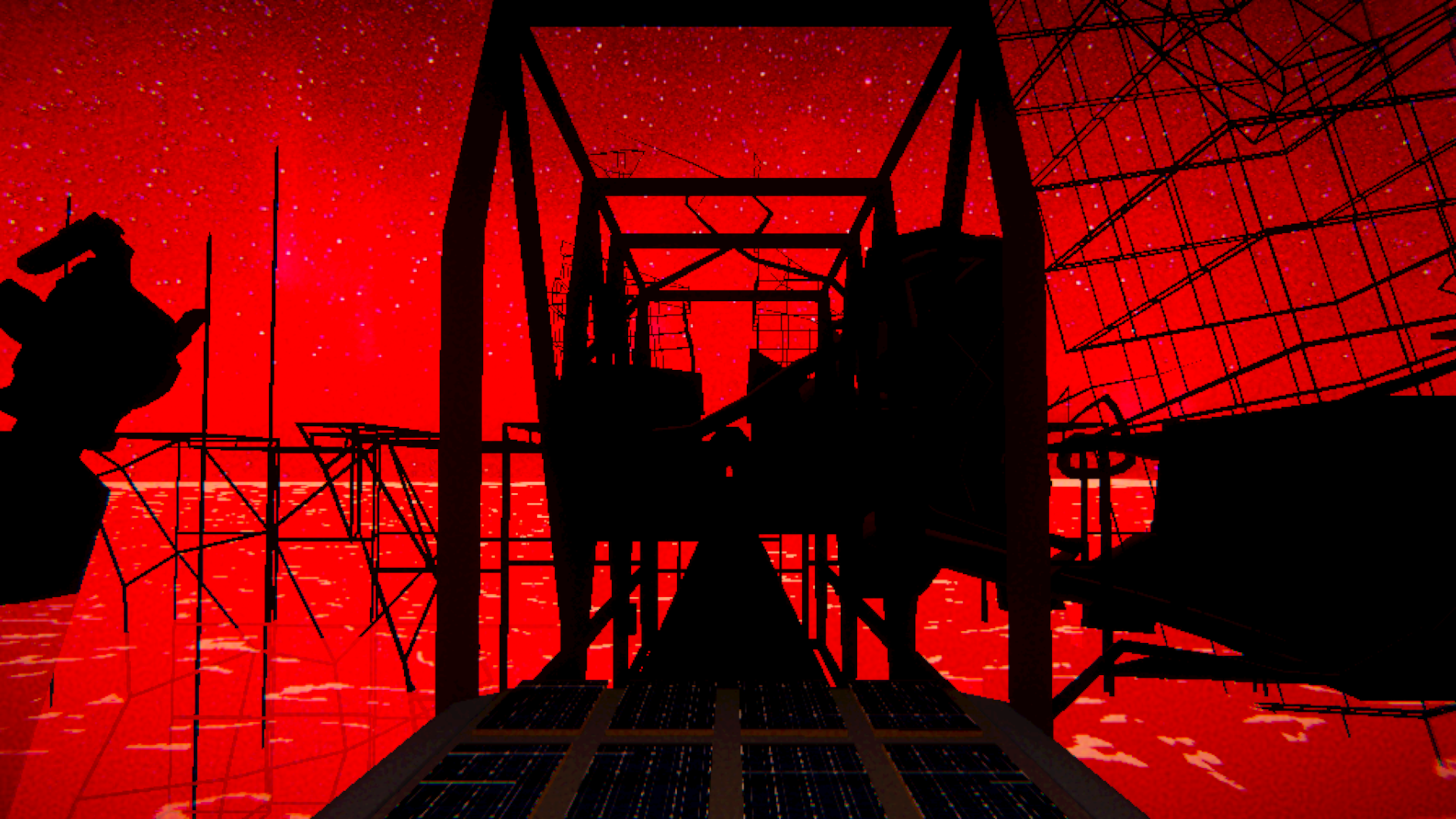

Umurangi Generation came to me at a time when it seemed like the world was at its imminent end: I had just moved across the U.S. and away from everyone I had known, the Covid-19 pandemic had only just begun, and I was terrified of what the 2020 U.S. presidential election would bring. As I played through it, I took photos of kaiju, graffiti, colonial occupation, parties, police brutality, and a penguin. I found its mediation of fascism, colonialism, police violence, and climate change both unsettling and comforting. It felt like all parts of me were being seen: the nerd who wants to understand the processes of fascism and colonialism, the organizer who wants to use that knowledge to dismantle those systems, and the artist who sometimes just needs to take a photo of a penguin to remind themself that they are human. The game showed me an a messy, angry, cathartic ethic of care during my own time of need.i

This essay is the first in a two-part series examining Umurangi Generation and it’s relationship to trauma and memory.

The Future Traumas of Settler Environmentalism

It’s November 7th, 2020. The U.S. presidential race has just been called for Joe Biden, but I find little relief in the outcome. Some of the tension in my shoulders has finally let go after years of a seemingly non-stop landslide into fascism, but an ember of fury remains embedded in the muscle tissue. As I walk past a liquor store, I see people dancing in line, but their joy fails to infect me. All I can think about is how, at best, things will be slightly less stressful, and at worst… the self that existed in 2020 could not imagine how bad it would get. I recognize that for some this is a critical celebration; they know there are still going to be problems and need a moment to celebrate even the tiniest win. But the hubris of the people who think that everything is fixed keeps the enraged embers alight inside me.

Swallowing down the fire, I sit on a bench and stare blankly at the trees in the park. The trees burn away, and suddenly it is weeks later. In front of my computer, I see that Umurangi Generation has a new set of levels called The Macro DLC, released on November 7th, 2020. Umurangi Generation is, like myself, still furious.

It’s November 27th, 2021. Reading Kidman and O’Malley, they tell me that counter-memories are “social memories that exist outside [and as a result challenge] the historical canon.”ii They add that within Māori groups, counter-memories have been passed down via stories of the past tied to specific landmarks. I pause to consider how this relates to Umurangi Generation, a fictional game where giant kaiju destroy entire cities. A game where Evangelion style mechs are built fight on behalf of the state, only to be turned on civilians. Māori social memories are based on history, and Umurangi Generation is a Māori game, but a futuristic fiction.

As I take pictures of the Kaiju, of the destruction of Aotearoa, and of military violence against civilians, trauma upon trauma rains down. It’s weeks earlier and the trees are burning by the park bench again. I came here to read Cho’s words, “The disintegration of progressive time and the inability to locate (and thereby erase) the content of memory play out in such a way that the distinctions between the actual interview and the imagined story become less important than the traumatic effects communicated by the words themselves.”iii Trauma narratives are not about reproducing reality or linear time, they are about mediating the processes and effects of trauma. Umurangi Generation does not tell us about the timeline of history, but about the traumas of history.

The game highlights these historical traumas not by fictionalizing the past, but by reshaping our stories of the future. By countering techno-utopian predictions of constant technological revolution, Umurangi Generation counters the progress narrative of history. The game confronts players with images of our own destruction, a direct result of our relationship to the environment, and asks, “how we relate with our sensual and affective being to catastrophic events the we may predict but that have not yet happened, yet of which we know that, if they happen, it is because of the footprints our generation left on the planet.”iv I’ve gotten ahead of myself, let me explain.

I don’t remember when, but I was going for a walk in Salt Lake City and had paused to stare at the mountains in front of me. They were shrouded by smog, giving the hazy peaks a vague sense of melancholy. As I stood there, a group walked past me discussing carbon offset practices as a solution to the city’s toxic air. I thought to myself, the fucking hubris. Choking on the fumes filling up the valley, I felt the sting of settler environmentalism scar my lungs. I remember Paperson telling me that settler environmentalism views “’nature’ as rape-able, and of ‘development’ as the normalized aim of modernity.”v We pollute the planet so we can continue to develop new land and technologies. Then, via carbon offset practices, we assume we can force that pollution back down the planet’s throat through the beings we plant in the ground (it doesn’t work).vi

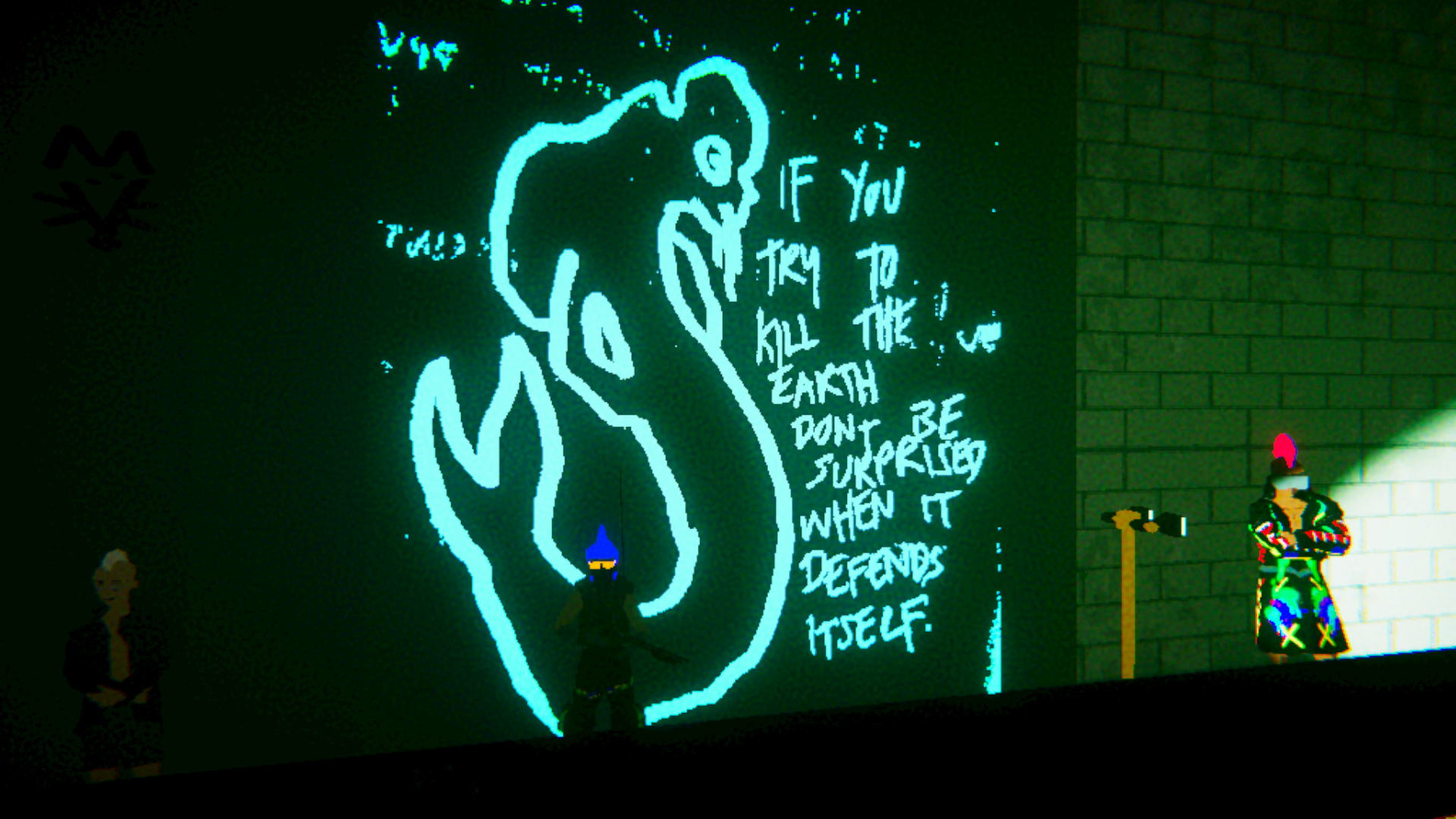

Umurangi Generation is warning us with its prediction of the future: the hubris of our settler environmentalism will be our death. Tech mogul Jeff Bezos wants to pollute space, to literally fight the gravity of the Earth we stand on to add to an already immense pile of space trash which orbits the earth.vii The hubris. Elon Musk doesn’t mind blowing up a rocket on the wildlife of protected lands for “science.”viii The hubris. In Umurangi Generation, the United Nations will fight the kaiju with giant mechs rather than solve the environmental devastation that caused the kaiju in the first place. The ridiculous levels of hubris. Umurangi Generation puts it best, “if you try to kill the earth, don’t be surprised when it defends itself.”

It is 2025 and I sit in my room, feeling that Umurangi Generation has never been more prescient. The trees are still on fire. The smog is still choking me. New atrocities come daily. Settler environmentalism remains the same domineering force.

But I know there are other ways of relating to the world. Indigenous environmentalists ask us to think differently about our environment and the land, replacing possession with “custodianship, a caretaking for future generations, and an acknowledgment of the temporariness of an individual human life.”ix Rather than using “patriarchal domination, land is respected for having its own sovereignty,”x which we do not bend to our will but work with in a mutually beneficial relationship. It is not enough to change our mindset to include more “sustainable” technological progress. We must change the very way we relate to the environment around us.

It is 2025 and I sit by the river, feeling the sounds of the rushing water reverberate through my bones. It asks what I need, and I tell it that it’s gifts have already been received: the embers of fury inside me have been doused, if only for a moment. We pause and let the chirps of nearby birds fill the space. The wind gently breezes past, rustling leaves before settling down once again. I sit up. “So,” I ask, “what do you need?”

Endnotes

i Rachel Alicia Griffin, “Navigating the Politics of Identity/Identites and Exploring the Promise of Critical Love,” in Identity Research and Communication: Intercultural Reflections and Future Directions, ed. Nilanjana Bardhan and Mark P. Orbe (Lexington Books, 2012), 216.

ii Joanna Kidman and Vincent O’Malley, “Questioning the Canon: Colonial History, Counter-Memory and Youth Activism,”Memory Studies13, no. 4 (August 2020): 538, https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698017749980.

iii Grace M. Cho, “A Genealogy of Trauma,” in Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War (Minneapolis ; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), “A Genealogy of Trauma,” 50.

iv Gabriele Schwab, “Hiroshima’s Ghostly Shadow,” inRadioactive Ghosts, Posthumanities, vol. 61 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020),, 206–7.

v La Paperson, “A Ghetto Land Pedagogy: An Antidote for Settler Environmentalism,”Environmental Education Research20, no. 1 (January 2, 2014): 117, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.865115.

vi Keith Hyams and Tina Fawcett, “The Ethics of Carbon Offsetting,” WIREs Climate Change 4, no. 2 (2013): 91–98, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.207; Eric Niiler, “Do Carbon Offsets Really Work? It Depends on the Details,” Wired, accessed December 13, 2021, https://www.wired.com/story/do-carbon-offsets-really-work-it-depends-on-the-details/; Doug Struck, “Buying Carbon Offsets May Ease Eco-Guilt but Not Global Warming,” Christian Science Monitor, April 20, 2010, https://www.csmonitor.com/Environment/2010/0420/Buying-carbon-offsets-may-ease-eco-guilt-but-not-global-warming.

vii Justine Calma, “Jeff Bezos Eyes Space as a New ‘Sacrifice Zone,’” The Verge, July 21, 2021, https://www.theverge.com/2021/7/21/22587249/jeff-bezos-space-pollution-industry-sacrifice-zone-amazon-environmental-justice.

viii Dianna Wray, “Elon Musk’s Spacex Launch Site Threatens Wildlife, Texas Environmental Groups Say,” The Guardian, September 5, 2021, sec. Environment, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/05/texas-spacex-elon-musk-environment-wildlife.

ix Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, “He Wahine, He Whenua: Maori Women and the Environment,” in Reclaim the Earth: Women Speak Out for Life on Earth, ed. Leonie Caldecott and Stephanie Leland (London: The Women’s Press Limited, 1983), 138.

x Ashley Cordes, “Meeting Place: Bringing Native Feminisms to Bear on Borders of Cyberspace,” Feminist Media Studies 20, no. 2 (February 17, 2020): 287, https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1720347.